Translator’s Preface

Not too long ago I came across a newspaper column discussing the guru-student relationship. The columnist wrote, many a times he gave a seminar on Buddhism, he encountered a question irrelevant to the topic of discussion, that if one’s master is not what one had expected, especially in terms of his conduct, what is one to do?

The question seems benign enough, the columnist went on to comment on the unreal expectations that students have on the teacher and the teacher’s moral standard. The cynicism, no doubt, stems from the scandals across many religious organizations in recent years. From time to time, we hear news of misconduct from leaders, clergies, and masters, the exact people whom we expect to be role models, setting the code of conduct for the ordinary folk. It appears that every religion has such scandals, regardless of geography or ethnicity. Such news occurs at a rate that it is difficult to summon up confidence or enthusiasm for leaders in general. The impact is widespread, whether it is communal, religious, or political.

Erring the Side of Appearance

What I find interesting though is that, while the article did not perpetuate falsehood, it presents a form of partial truth. By partial truth, there have indeed been leaders who have abused their position of power. What the article failed to articulate is the significance of establishing of a guru-student relationship. Much like an apprenticeship in the ordinary sense, a unique set of skills is passed such that both workmanship and tradition are kept alive. And in that sense, being accepted into the apprenticeship is also not unlike being accepted into a family. By opting to highlight the negative behaviour of a minority few, the columnist has greatly diminished the importance of the guru-student relationship.

From time to time, my teacher would comment on his students’ conduct, that we err on the side of the phenomena (顯現邊 or the extreme of the appearance). By phenomena, there exists an appearance, or something being perceived. If one chooses to focus on what is being perceived, one has in other words also erred on the side of consciousness.

One may ask, what else is there other than consciousness?

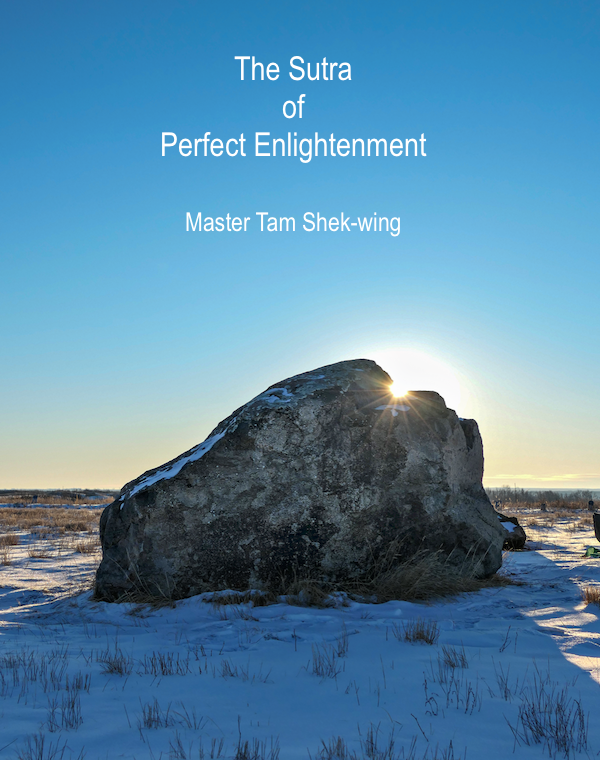

This is also why... Show more. This is also why I find the column hurtful. I don’t mean hurtful to me personally, but highlighting a partial truth, what is partial is taken to represent the whole. In the exact way my teacher’s comment on erring on the side of the phenomena, the readers are being led to focus on the partial, forgetting that there is always something beyond. After the publication of The Dharani of Entering Non-conceptuality, it has always been clear to me that the next book should be a text with an emphasis on the practice. While Buddha had said that the authentic Buddhist practice is inclusive of the teaching, the practice, and the realization (有說有修有證), I had always found the books that were published, at least the ones that I was involved in, erred on the side of being theoretical. By theoretical, in terms of the triad of teaching, practice, and actualization, the teaching seemed abundant, it was the connection between teaching (wording) to the latter two that appeared vague. Once I discovered I was not the only one. At one time a reader wrote directly to my teacher saying essentially the same thing. The reader wrote, “Could you be a bit more concrete?” something that none of us students would dare to ask. Upon some consideration, my teacher began posting a weekly column on Sutra of Perfect Enlightenment. The intend was to present a general enough overview that the reader has a glimpse of what authentic Buddhism is. That was in 2016. My teacher’s point was that with the vastness of the Buddhist Canon, each scripture has its emphasis in terms of the teaching, the practice, and the realization. Because they each have a specific emphasis, it is easy to take the partial to represent the whole. One of my teacher’s favorite examples is the relationship between Yogacara and Consciousness-Only, both are traditions taught during the third dharma-chakra. In the scripture, the two terms are sometimes used interchangeably but they are not equivalent. One is the general framework and the other presents an aspect of it. Mistaking the two is like missing the forest for the trees. Imagine the same confusion mistaking Einstein’s theory of relativity with Newtonian physics. This would be disastrous in the world of physics. Another interesting example is... Show more. Another interesting example is the case of “shedding body and mind” (身心脫落). The Sutra of Perfect Enlightenment was deemed “a forgery” by Dōgen, the founder of Soto Zen. It was deemed inauthentic because in it, in answering the questions on the way towards enlightenment, Buddha introduced three meditations (śamatha, samāpatti, dhyāna), and through various combinations, he further established twenty-five expedient practices to suit the different stages of practice, and by Dōgen’s reasoning, counter to the notion of “shedding body and mind.” But what is “shedding of body and mind”? By insisting on what “shedding body and mind” is, unwittingly, Dōgen trapped himself into an ego self (obvious) and a phenomenal self (what is or is not), which is also antithesis to what he advocated. In retrospect, it is ironic for the previous book was in part about “entering non-conceptuality.” One time a friend of mine asked me how could anything not be conceptual? The scripture contains pointers going from conceptuality to non-conceptuality. The connection is there. It is up to the reader to make the effort to connect the dots through practice and ultimately realization. This is in line with the Nyingma tradition where the practice comes in four layers: outer, where everything is perceived as objectified, where the subject self is separated from the objective phenomena; inner, where the outer object is contemplated as a perception; secret, all things inner are easily outer; and the utmost secret. Therefore, through the bridge of entering non-conceptuality, one enters the realm of coalescing wisdom and consciousness, gradually for some, and suddenly for others. Gradual or sudden, everything possesses the Buddha-Within. This is also why my teacher insists on reiterating the Buddha-Within as the coalescent realm of wisdom and consciousness. It is easy to allow consciousness (or what is apparent to us) to hijack everything. Buddha warned his students to abide by the four reliances in an attempt to prevent them from allowing what is apparent or what is conceptual to hijack everything. In Dōgen’s case, he let his reasoning (ego self and dharma self) take precedence over the teaching. By calling a scripture a forgery, the expedient practices become lost to many, even if their aptitude was suited to the practice. In the columnist’s case, the article serves to compound on the existing cynicism and mistrust in the reader population. This is unfortunate, now that we are three years into the pandemic, there is only more and more mistrust and confusion between people. The good news, though, is that the mistrust and confusion are only phenomenal, an appearance. What appears is not a substitute of what is within, in the same way that trees are not the forest, but they are also notnot the forest. In the Sutra of Perfect Enlightenment, Buddha used a fabulous turn-of-phrase, 器中鍠. 器中鍠 literally means the sound (鍠) in/of (中) an instrument (器). An instrument with all its physicality naturally embeds within it the sound. My teacher wrote: In the objective realm... Show more. In the objective realm, the world of experiences and the appearances of body and mind, the scripture compares them to the sound of an instrument (器中鍠), where the instrument itself does not obstruct the sound. The sound penetrates to the outside, a listener is instantly aware, enjoying the appearance of music, and the appearance of body and mind listening to the music. At this point if there is still the appearance of the instrument, then it is no longer “without awareness of the illumination of enlightenment,” because it is still “depending on all sorts of obstructions.” Many good musicians fall into this trap. This is from an alto instrument, that is from a bass instrument; this is woodwind, that is brass. It is as if a clear distinction has been made, but one has also become trapped by the mutual obstruction of various instruments. What is heard is no longer the sound (器中鍠), but rather, it becomes which instrument producing what sound, no longer transcending obstructions and non-obstruction. It is not easy to enter the realm of dhyāna, because it is a realm where “affliction and nirvāṇa [are] not hindering each other.” Using the music analogy, it is the sound of music and “without awareness of the illumination of enlightenment” do not hinder each other. The sound of music is analogous to affliction, the awareness of the illumination is analogous to nirvāṇa, hence they are said to “not hindering each other.” With this note, I hope the translation serves the purpose of highlighting the practice, where Buddha illustrated three, and with the three, further established twenty-five. And because by analogy of the sound in the bell or 器中鍠, it is inclusive of the teaching, the practice and the realization/actualization. While the language still has to abide by the Buddhist lingo, it is my hope that the Buddhist practice has become more graspable, clearing the confusion due to consciousness and conceptuality, allowing wisdom to shine through, especially in the world we live in. Entering Winter Solstice, courtesy of Tom Wilson, 2021. Early in the year, Tom Wilson, a friend of my husband, offers his photograph to me as a book cover. It captures a ray of sunlight at the moment entering winter solstice. My husband liked it so much that he asked if I could use it for the next book. The photographer said yes without thinking. In retrospect, not only is it the spirit of photography, it is also the spirit of the Buddhist practice. Sharing one’s luck like marbles or baseball cards. Or whatever treasure one has. This is also to echo the concluding section on dissemination, where, contrary to taking a sectarian view, Buddha had instructed on the practice, sudden or gradual alike, it is “like a great body of water which does not deny the entrance of any small stream.” On this note, may our world be liberated from names of violence and warfare, disasters and sickness. Vivian TsangMissing the Forest for the Trees

The Sound of the Bell

Toronto, Canada

Oct. 8, 2022